Case Study: How Cathedral Pines Proved That Wildfire Mitigation Works

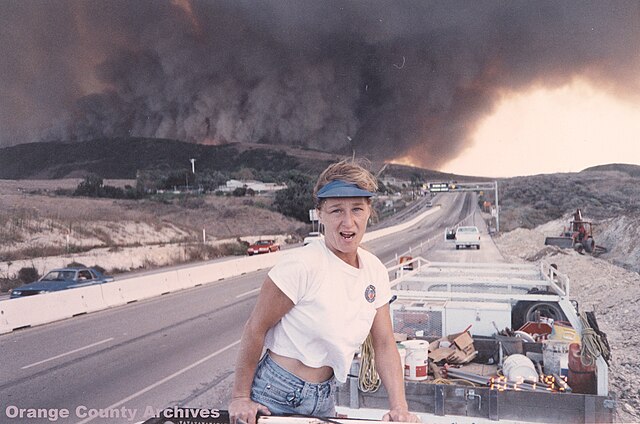

In June 2013, the Black Forest Fire erupted near Colorado Springs, Colorado, becoming the most destructive wildfire in state history at the time. The fire scorched over 14,000 acres, destroyed more than 500 homes, and tragically took two lives¹. However, amid the devastation, one community—Cathedral Pines—stood as a remarkable case study in wildfire mitigation. Through proactive fuel reduction, strategic land management, and community-wide preparation, Cathedral Pines suffered minimal damage, proving that wildfire home hardening efforts are not just theoretical—they work.

This case had a significant impact on Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) science, influencing best practices in fire-prone communities and demonstrating that home survivability is not random but a direct result of preparation.

Before the construction of homes, the developer of Cathedral Pines incorporated aggressive fire mitigation strategies. This included:

- Forest thinning—removing unhealthy trees and excessive undergrowth to reduce fire intensity.

- Fuel load reduction—clearing dead vegetation and ladder fuels to prevent fire from reaching tree canopies.

- Strategic home placement—ensuring that homes had proper defensible space and that streets were designed to allow for emergency access.

When the Black Forest Fire reached the community, its intensity dramatically decreased. Instead of engulfing entire homes as it did in surrounding areas, the flames dropped to the ground, burning only one house near unmanaged forest land outside Cathedral Pines².

This was a landmark moment in WUI science—not just anecdotal proof but a large-scale, real-world test case showing that these methods save homes.

The Black Forest Fire and Cathedral Pines case study reinforced key fire mitigation principles that are now widely accepted in WUI science³:

1. Proactive Mitigation is More Effective Than Reactive Firefighting.

- Fire-resistant landscaping, proper spacing between structures, and ember-resistant construction significantly reduce structure ignition.

- Firefighters are more likely to protect homes that have defensible space and survivability potential.

2. Fuel Reduction Works.

- Many WUI communities hesitate to thin forests due to aesthetic or environmental concerns, but Cathedral Pines proved that well-managed landscapes slow fire spread and lower flame intensity.

- Studies after the fire showed that areas with higher fuel loads suffered catastrophic loss, while areas with strategic thinning saw far lower destruction⁴.

3. A Single Home’s Mitigation Efforts Aren’t Enough—Community-Wide Action is Required.

- Cathedral Pines was successful because fuel reduction was done at a community scale.

- A single fire-hardened home cannot survive if surrounding vegetation and structures ignite easily.

The Cathedral Pines case study is proof that wildfire destruction isn’t inevitable—it is a direct consequence of preparation (or lack of it). Homeowners in fire-prone areas should take these key lessons seriously:

- Start mitigation efforts now. Wildfire mitigation is most effective before a fire threatens your home.

- Work with your neighbors. A hardened home can still burn if its surroundings are highly flammable.

- Regular maintenance is critical. Removing excess vegetation once is not enough—fire preparedness is an ongoing process.

Cathedral Pines was not lucky—it was prepared. And that preparation made all the difference.

The 2013 Black Forest Fire solidified WUI mitigation science as a critical factor in home survival. The Cathedral Pines case should serve as a model for every high-risk wildfire community in the country. The science is clear: Mitigation works, and preparation is the key to home survival.

Sources

¹ “Black Forest Fire: Colorado’s Most Destructive Wildfire,” Colorado Division of Fire Prevention and Control.

² “Why One Colorado Community Survived the Black Forest Fire,” CAI-RMC.

³ “Wildfire Mitigation Lessons from the Black Forest Fire,” International Association of Wildland Fire.

⁴ “Post-Fire Analysis of the Black Forest Fire,” U.S. Forest Service.